Howard, who speaks slowly and with a “cured” stutterer’s affectation, asks me when I will die.

That’s not exactly what he says, it’s what he wishes to ask, but can’t.

“And your parents? Did either of them die of a heart attack, stroke or cancer…before the age of 65?”

Before?

Of those diseases?

“No.”

They are dead though. They never turned 70. I don’t say this.

He asks the wrong questions.

He wants to hear good things. It means money for him. I know this. A commission. Continued employment. A life. A monthly check from us, against what we hope won’t happen.

It means “life insurance” for me. I know this. As much as it can be known.

The trick is only to answer what is asked.

I keep trying.

”Your height and weight?”

Ugh.

“Has a doctor diagnosed you with any of the following in the last 10 years?”

Wrong question again. Answer is no. Not in the last 10 years.

Keep trying, Howard.

“How much life insurance do you want?”

Long pause. Bile rises in throat. Burns. Want. Want. Not sure I want this at all.

“How much…ma’am?”

“Yes?”

“Life insurance. How big a policy?”

“How do people usually—“

“Well, you take your income.”

“My income. That’s my value. My income. Are you sure?”

“You know—if you don’t have a job, you do things that would need to be done, you know? So you figure out how much it would cost for someone else to do that and you multiply by—“

“I multiply?”

“Ma’am?”

“Yes?”

“Yes, you take those things—you know, child care and cleaning and things that other people could do, and you multiply it—“

“I multiply it.”

My head is reeling. My heart shatters into a million trillion gazillion little pieces. My value. Multiplied by years I’m not there. My life expectancy, by my weight. My age. When my parents died.

The wrong questions.

“Ma’am—your husband has filled a lot of this out for you.”

“He has?”

“Yes.” My wifely duties, multiplied by sitters so he can go date and replace me?

“Do you want me to go over it?”

“No. I don’t think so. “

“Okay, then, ma’am, let’s just keep going then, we are almost done.”

“We are?”

“Yes, I think so.”

“Okay.”

“So I need to set up an appointment for someone to come out and take your blood.”

“Of course.”

“And you’ll need to sign.”

“Of course.” Sign, in blood, the contract.

“And that will be it.”

“Right.”

“As soon as we figure out how big a policy.”

“Right.” Pregnant pause. “That’s the trick, isn’t it?”

“Ma’am?”

“That’s the trick.”

“I’m sorry, ma’am, I don’t understand.”

“How to value someone. I mean, Howard — How much for your mom?”

“Ma’am?”

“How much?”

“What do you mean? How much would you pay for when she isn’t there?”

“Ma’am, I’m not sure you get –“

“Really? Isn’t that what you are asking me? To prepay for? In case I’m not there? Someone else?”

“Ma’am, this is just life insurance.”

“Howard, you are very young, aren’t you?”

“Ma’am?”

“Not even 25 yet, right? Your grandparents still alive?”

“Ma’am? Do you want to talk to my supervisor?”

“No, Howard. I don’t need your supervisor.”

I take out a paper and pencil and my calendar – start putting dollar signs next to the cramped and crowded, boxes – adding it up.

My life, my parents, dead in their 60s, the things my doctors had diagnosed me with more than 10 years ago.

My hot pink calculator works the numbers, straight to “E.”

My over sharpened pencil tip breaks (NOTE: mess with the electric pencil sharpener). I take the pencil and cleave it, break it in half, cleanly in the middle. Now I have 2 pencils. That’s power.

The evening continues. Dinner, homework, kids ready for bed.

Then the husband speaks as I settle in the couch to watch the flickering images of the TV.

“Did you talk to the guy?”

“The guy?”

“From the insurance?”

“Howard? “

“I don’t know his name.”

“Yeah, I talked to him.”

“And?”

“He’s sending stuff.”

“Oh, good. Check that off.”

“I don’t want to know.”

“What?”

“The policy.”

“What?”

“I don’t want to know the size.”

“Oh, I just got –“

“I don’t want to know.”

“Okay.”

“Can you get the kids off tomorrow?”

“Yeah. Why? What’s up?”

In my head, I hear myself say my supervisor has called a meeting. But I don’t say that out loud. It isn’t true.

“I have a thing.”

“A thing?”

“Yeah.”

“Early.”

“Okay.”

“You alright?”

“I have no idea.”

“Doctor?”

“No. Well, yeah, sort of. Has to be first thing. They said.”

“Okay.”

It was that easy. The thought in my head. The supervisor I had to get out of the house—away from this to figure it out. I could do it. I just had to leave really really early.

And I didn’t need a pencil, or a calculator. Of this I was sure.

I didn’t even need to set an alarm. I sat straight up in bed at 3am, awake. Grabbed some favorite, ancient clothes, an old geeta burner shirt, clam diggers made of the softest cotton. I didn’t need a magic bag full of emergency kid’s supplies, band aids, tissues, restaurant toys. I needed very little.

The math.

When my parents were 20, 25 years older than I was at this very minute, they were dead.

15 years ago, doctors had told me all sorts of things were wrong with me, but

for the last 10? I’d been fine—busy, caring for small children who insisted on growing every day.

I jumped into my car, and drove. Somehow I knew if I could change things, this day, it would matter.

New math, number of miles times speed limit over a full tank.

I drive, and I drive east. To the ocean. To Rehoboth. If I could get to the beach. If I could get to the sand and the endless, rhythmic crashing of the enormous powerful ocean onto the sand, I know it would all make sense.

I had this. At this time of day there would be no traffic. I have a meeting. I smile.

As I drive, the fear falls off. I leave it by the roadside.

The numbers that chase each other through my head, slow.

Over the enormous suspension bay bridge, I turn on music. Beach music. Seems right. The calypso steel drums.

It is still very dark, but I can sense my heart reassembling, I can feel it.

The flat land of farms speeds by me, the music draws me east like a tractor beam.

I blink, and I can barely remember why I was going to the beach, but I blink again and pull into one of the new metered spaces on Rehoboth Avenue. Time ticks down.

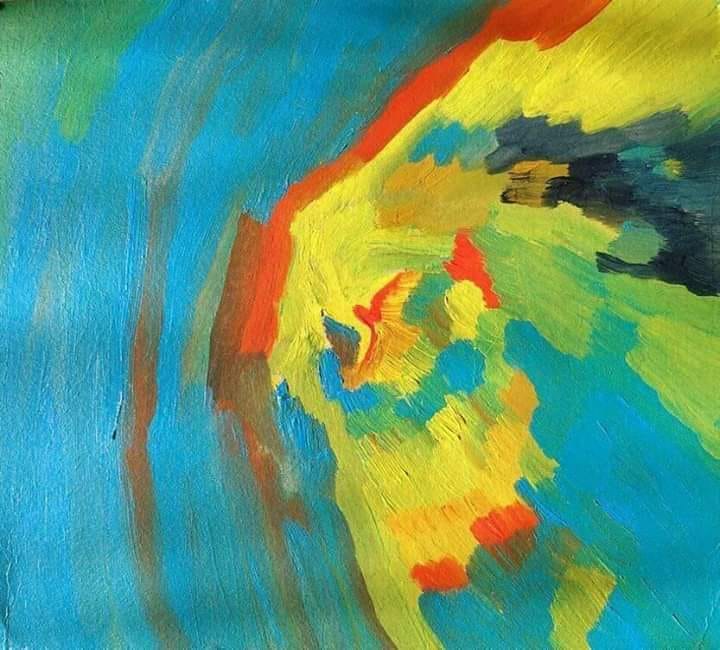

I get out and walk straight for the surf. Past the bandstand. Past the Dolle’s sign. Past the beach grass. The pink light is beginning to come up over the blue grey ocean.

Toss my shoes back toward the sand and away from the sea – two gulls caw in search of Boardwalk fries.

Stand before the ocean in silence, in the space between — the meditative space.

Stare out into the sea for an answer. I face the sun as it begins to peek over the horizon.

In the next minute, the sun explodes over the ocean like a kaleidoscope of fractured color that exactly matches my newly reorganized heart – as if they were both identical mosaics of Indian mirrored sequins.

Just as suddenly as my heart shines and the sky sparkles, as if in a spasm, my arms meet overhead, my left left leg lifts.

I smile.

A pod of dolphins leaps by, joyfully billowing spray. A celebration.

The ocean pounds, so much bigger and more powerful than me.

The pounding is my heart.

I know the answer.

I am alive.

The world is still Beautiful. The salt air felt right and restorative. It is a place I could be in forever. A moment. Held in my heart and shooting out my fingertips.

It has been over 15 years ago—but the thing that had evened out the illnesses, time, space. Breathing. Maybe even some yoga.

Yes.

A rainbow kite flies over head. Bikes thump on the boardwalk. A lab chases a Frisbee into the surf.

My supervisor. Called a meeting. The message? Greet the day. Salute the sun.

Okay then.

Arms up, overhead, left leg slides up the right leg. I can hear the instructions clearly in my head. Audibly. Forward fold.

Plank. Grasshopper, cobra. Dog, child.

Come up.

Repeat.

Breathe.

This is

my

Life insurance.

©2021 Hildie S Block

All rights reserved

Thank you for sharing the beauty and inspiration: