Stepping into Gandhi’s Sandals

Washington and Gandhi

We entered Pyzzz (pronounced like “pies”), a Putnam, CT, pizza restaurant. Wearing suit and tie, I accompanied George Washington dressed in his military uniform—epaulets, tri-corner hat, powdered wig, boots, and sword. After ordering, we waited for dinner. We cut a memorable duo, Washington tall and regal and I a bespectacled school principal, described in a high school senior’s college essay as “a small balding man, a cross between Woody Allen and Gandhi.”

Eyes drawn to Carl Closs, customers asked: “How are you General Washington?” “Why are you in Putnam?” “Do you like Pyzzz’s pizza?” Closs replied, “Yes, this is my first pizza; I must tell Martha about it.” Amused by this fuss over Closs, I knew our first president never ate pizza; Italian immigrants brought it to America in the 19th century. Nonetheless, Washington’s 21st century incarnation enjoyed his meal. Responding to further customer scrutiny, he said, “Tonight, I speak at Woodstock Middle School. Please consider attending.” A seasoned character portrayer, Carl appeared to step effortlessly into Washington’s shoes, easily managing to reinforce the good reputation of the Father of Our Country.

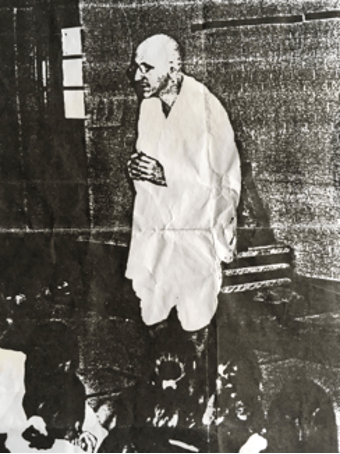

What does it mean to step into another’s shoes? Is it appropriate to try? Having myself frequently attempted to step into a great man’s sandals through portraying Mohandas Gandhi (1869-1948), a sideline I cultivated for students, teachers, churches, and social change groups, I harbor a genuine interest in these questions. Each time I step into my leather sandals, an Indian pair, the kind worn by Gandhi, I sense a kinship with him, a duty to be like him. My portrayal feels natural, hardly make-believe.

Sporting a loincloth (dhoti) and shaved head, I begin to sense an internal transformation. Next, I put on wire-rim glasses, labeled “Gandhi/John Lennon” in the catalogue of frames my optician consulted when I told him I needed spectacles like Gandhi’s. Once properly adorned, I am transported still closer to the brown-colored Indian I both admire and portray. I sense an interpersonal process, analogous to the physical principle of osmosis, seemingly diffusing Gandhi’s spirit and worldview throughout me. A Gandhi scholar who observed me in my role as Mahatma answering tough questions in my Gandhi voice, all the while wearing a dhoti in front of an adult audience at Brown University, said I “nailed” the impersonation. He told another witness to my performance, “Had I not known my history so well, I would’ve thought I was standing in the room with him.”

Clad skimpily as I exchange my horn-rim glasses for a pair with old-fashioned bendable wire temples behind the ears, I imagine Lennon’s and Gandhi’s faces, their eyes peering through circular lenses. I flash to a second similarity between these men—both shared a proclivity to bed down publicly with women to effect social change. In 1969, Lennon married Yoko Ono. They capitalized on the public’s engrossment with their marriage, together protesting war. Turning their honeymoon into a spectacle, they held a “bed-in,” inviting the press to their hotels in Amsterdam and Montreal, where Lennon and Ono lounged in bed beneath signs promoting peace and chatted with journalists about the futility of war.

Twenty-five years earlier, celibate Gandhi conducted a controversial, exploitative, and perverse experiment to confirm his ability to resist sexual arousal. His wife deceased, he slept naked beside teenage girls sixty years younger to prove he had achieved brahmacharya, celibate self-control, a precondition, he believed, to his perfecting devotion to nonviolence and effective management of the independence movement. Despite India’s patriarchal culture, some followers and family denounced this practice. Nevertheless, he continued these experiments until his death.

Gandhi’s bizarre behavior aside, I nonetheless find myself transformed when I squint through wire-rims and don other accoutrements that make me look like him. Channeling his virtuousness, his irksome eccentricities slide to the back of my mind; I become Gandhi, now able to embrace Lennon’s lyrics with Gandhian assuredness: “You may say I’m a dreamer / but I’m not the only one / I hope someday you’ll join us /And the world will live as one.” Imagine!

My portrayal presents a conundrum though, one with which white folks in America now grapple. American Caucasians, advantaged because of skin color, risk further demeaning people of color if they portray them. Recent revelations of white politicians wearing blackface have crystallized this question: In a white-dominant society, who possesses the moral authority to portray a brown or black person? I now ask: Can I justify my practice of portraying Gandhi?

These queries complicate my thinking, especially in light of the forty-year-old brouhaha regarding the legitimacy of ethnically unqualified actors portraying Gandhi. Criticism of filmmaker Richard Attenborough’s choice of Ben Kingsley to play Gandhi in the Oscar-winning film bearing the same name emerged in 1982. A light brown Englishman, Kingsley grew up in England, his father a Kenyan-born man of Indian descent and mother a white English actress. Critics assailed Attenborough for failing to cast an Indian from the subcontinent in the role.

Putting aside the issue of whites portraying people of color, Nathaniel Philbrick points to another, perhaps more fundamental, problem with attempts to portray people in history. Having met Dean Malissa, an official George Washington interpreter at Mount Vernon, Philbrick quotes Malissa: “The great frustration of my profession is that while I can study contemporary reports, consult everything that’s been written about the man, I can never truly inhabit his world, walk in his shoes, share his beliefs. It’s a humbling flaw.”[1]

Malissa’s admission should make every character interpreter wary of the enterprise, including me. Never having set foot in India, much less Gandhi’s India, I can never inhabit his world. My portrayal of Gandhi depends on books and reports about him, his own writings, and newsreels displaying his body language and manner of speech.

Gandhi and Me

Gandhi succumbed to an assassin’s bullet in 1948, but his work continues. Captivated by his life and philosophy, Rabindranath Tagore dubbed him Mahatma, an honorific meaning “Great Soul.” His magnetism still attracts disciples. Modern admirers oft apply his methods in human rights struggles—noncooperation, fasting, prayer, civil disobedience, and boycotts.

Would that I knew Gandhi directly, not just through biographies, his extensive writing, and Sir Richard Attenborough’s monumental 3½-hour Gandhi. I showed that film more than twenty times to students. They found Gandhi’s pioneering leadership of a nonviolent campaign against British colonialism astounding. He fused truth-seeking, integrity, and love into a nonviolent force—an amalgam for which he coined the term Satyagraha, soul force—a means to bend people’s hearts toward justice. His method induced devotees to exchange silent acceptance of colonial rule for militant, principled, nonviolent opposition. Of nonviolence, Gandhi said that it “is the supreme virtue of the brave,” adding, “Cowardice is wholly inconsistent with nonviolence…”[2] He taught this radical resistance by example and through tireless writing; his writings exceed ninety volumes. And among Indian historians, his successful challenge of British occupation earned him the epithet, “Father of Our Nation.”

To portray Gandhi invites self-reflection. Commenting on his evolution into effective change agent and revered holy man, he said, “I have not the shadow of a doubt that any man or woman can achieve what I have, if he or she would make the same effort and cultivate the same hope and faith.”[3] I agree. Therein the rub: Why don’t more of us make the same effort? Feeling instinctively comfortable adopting Gandhi’s persona, I am compelled to ask: Why have I failed to make the same full-throated effort to which he alludes? His leadership, a singular human achievement, makes him an aspirational model. How then do I understand his impact on me?

When I agreed to portray Gandhi, I had no idea if I could manage the role. Sally Rogers, a friend of mine teaching music in Pomfret Community School, a K-8 public school in eastern Connecticut, convinced me to try. A folk singer averaging some 150 gigs a year, sometimes performing on nationally broadcast A Prairie Home Companion, Sally, along with her husband, adopted two infant girls, one in 1989, the other three years later, both from India. To raise their kids without resorting to extensive daycare and babysitting, Sally retooled, becoming a music teacher in Pomfret where my wife and I live. In 1995, Sally approached me at the Vanilla Bean Café. She said, “Paul, I’m organizing a Cultural Awareness Week at my school, India this year’s theme. You know lots about Gandhi, would you talk about him to our middle-schoolers?”

After acknowledging how flattered to be asked, I replied, “No, I think I would bore middle-schoolers.” After inspecting my face and skinny body, Sally said, “Paul, you look like Gandhi, why don’t you become him?” Her invitation enticing, I agreed, despite my whiteness, to “become Gandhi,” fancying myself an actor, although having little reason to think so.

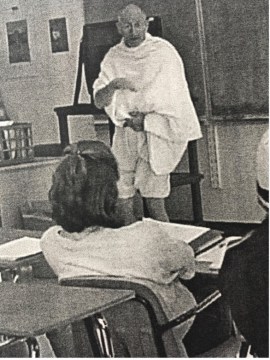

With only a few weeks to prepare, I grew anxious. Possessing little aptitude for memorizing theatrical lines, I determined a straight-out portrayal of Gandhi dependent on remembered lines only invited instant failure. Instead, I decided to become Gandhi, to connect with students by answering their questions about me, the Mahatma. I requested ninety minutes, although warned it likely too long for a hundred middle schoolers to endure. I insisted, imagining a protracted conversation without delivery of prepared lines. I intended a two-way street, the students and I thinking together and interacting.

Asking the teachers to prepare their students for my appearance, rather Gandhi’s visit, I recommended students read a Newsweek article identifying key details of Gandhi’s life. The middle-schoolers now familiar with highlights from Gandhi’s career covered in Newsweek, I anticipated three student questions: How did you feel on your march to the sea? Do you think it okay to break the law? How can people be nonviolent when others are hurting them?

Three film clips from Attenborough’s blockbuster dovetailed with these expected questions: (1) the Salt March of 1930, (2) Gandhi in court in 1922 pleading guilty to a charge of sedition after committing civil disobedience, and (3) Gandhi’s followers at the Dharasana Salt Works accepting police brutality without retaliating. If a student asked a question relating to any of these issues, I would reply in my Indian accent, “Well, I’m glad you asked. I have film footage that may help you understand.” These brief clips prompted many more student questions.

While I have committed civil disobedience myself, taught courses on nonviolence and social change, and served as a nonviolence trainer, I observe a chasm separating Gandhi’s life from mine. That alone throws into question the legitimacy of impersonating him. Portraying Gandhi arouses feelings of hypocrisy, believing I lead a life morally pale compared to his.

My first-time portraying Gandhi, I noticed, upon showing the film clip of him in the courtroom, middle-schoolers feverishly looking at me then returning to the screen, necks bending between the two, eyes incredulous, as if thinking, “He’s the real deal.” I must admit that I’m an uncanny Gandhi double, white skin aside, when fully attired, chest bare and head shaved to peach-fuzz length, a haircut that reliably invites my wife’s displeasure: “Paul, you could wear a bald cap.” I blurt back, “But I take seriously my portrayal of Gandhi, feeling most liberated to portray him without a latex cap.” With head shaved, I look like him, at least “a dead ringer for Ben Kingsley’s Gandhi” as a friend reported after watching Attenborough’s movie.

Gandhi’s spiritual practices enabled him to conquer selfishness, the allure of ego; I have not achieved such liberation. I judge myself as closer to the “Great Impostor” than “Great Soul.” Gandhi’s guidebook, the Bhagavad-Gita, taught selfless compassion, a preachment identical with essential elements in Jesus’ teachings.” One passage expounds:

They are forever free who renounce all selfish

desires and break away from the ego-cage of

“I,” “me,” and “mine” to be united with the

Lord. This is the supreme state. Attain to this,

and pass from death to immortality.[4]

“Attain to this,” such attainment arguably the central accomplishment of his life, allowed Gandhi to approach his death fearlessly, to make decisions during the Indian independence campaign without concern for damage to his popularity or threats to his life. Having escaped the “ego-cage of “I,” “me,” and “mine,” he, like Jesus, allowed love to trump expediency, and release from that cage also liberated him to risk death.

More than once he called off an advertised protest of colossal proportions, opposing many movement-organizing insiders and an angry public’s desire for doing “something” immediately. When calling off an action, he recognized cancellation risked subverting his leadership and defusing the movement. In 1922, Gandhi elected to call off the India-wide noncooperation movement that challenged the 1921 legislation known as the Rowlatt Act, a law permitting the British occupiers to imprison for two years anyone in India “suspected” of violent acts or the threat of violent acts. This draconian legislation gave India’s British rulers power to interfere with all revolutionary activities.

Advent of the Chauri Chaura riots, however, led Gandhi to sense the movement slipping from its nonviolent moorings. Despite the Rowlatt Act—Britain’s effort to destroy the Indian thrust for independence—Gandhi prevailed, undeterred by fellow activists critical of him calling off the nationwide noncooperation. Almost single-handedly, by suspending the resistance and fasting for three weeks, he quieted rioting mobs. Still, the British sent him to prison for six years.

Ethically and spiritually exceptional, Gandhi entreats us to imitate him, but any honest attempt to be like him requires a radical departure from the life most of us lead. Like Gandhi, I believe that anyone could achieve what he has, if willing “to make the same effort and cultivate the same hope and faith.”[5] Whenever I portray Gandhi, I sense that fissure separating his self-discipline from my anemic resolve to incorporate intensive spiritual exercise into my schedule. His success issued directly from disciplined contemplative practices. Leaving such diffidence aside, when I portray Gandhi, my white privilege notwithstanding, I am indeed more than a fragile, shadow incarnation of him; I sense something more robust, allowing me to portray him with ease and conviction, as if he animates my physical-spiritual self. What is this sensation?

Becoming a Gandhi Portrayer

Gunned down in 1948, Gandhi died two years before my birth. Occasionally, I wonder if reincarnation can be partial, just enough “soul substance” moving from his body to the next, in this case mine, depositing a touch of “Gandhiness.” Resisting the “psychobabbling” temptation to consider “partial reincarnation” to explain the ease with which I don the dhoti, I resort to my upbringing, believing Gandhi’s adult life comports with church teachings I absorbed from the pastor of the Dutch Reformed church on Staten Island to which my parents belonged between my first and fourteenth birthdays. Our minister encouraged his parishioners to oppose racism, engage in activities to address poverty, and view such efforts as consistent with Jesus’ teachings. I learned to consider Jesus a revolutionary God-Man who battled injustice, a model to emulate.

As a youngster, I grew fond of the idea of becoming a minister. Hospitalized for nine months of my first year of life, having undergone five major surgeries, I returned home expected to die. My parents later suggested to me that I owed a debt to the medical community, God, or both. Encouraged to think of becoming a physician or minister, I never felt drawn to medicine, but ministry appealed to me. In high school I developed theological interests, and at college I took enough courses in religion to major in it, though settling on philosophy.

Coming of age during an era of movements against racial injustice, the war in Vietnam, and gender inequality, I sensed the emergence of the 1960s as a distinctive decade, one of radical social change. I embraced it. Graduating from college in 1972, I began a teaching career in a Quaker secondary school west of Philadelphia. I taught religion. My education in human rights, religion, nonviolence, and anti-war themes intensified. I decided to apply to theological school, imagining a career in urban ministry, but in 1974 I turned down acceptance at a seminary in favor of teaching religion at a Quaker high school in Rhode Island.

Upon arriving in Providence, already an admirer of Gandhi, I soon joined a local nonviolence study group and assumed the clerkship of a New England-wide peace committee, an arm of the American Friends Service Committee. A teaching colleague introduced me to Gandhi, Attenborough’s epic film. Showing it to my students, I endeavored to deepen my knowledge of the Mahatma. I understood the similarity between the moral teachings of Jesus and Gandhi. A Hindu, Gandhi had an artist’s representation of Jesus on his ashram wall. Gandhi said that the teaching of nonviolence in Jesus’ “Sermon on the Mount” went straight to his heart: “It is that sermon which has endeared Jesus to me.”[6] And Martin Luther King, Jr., a Christian clergyman since 1948, went to India in 1959 to study Gandhian nonviolence.

Years later when Sally Rogers asked me to become Gandhi, it seemed like a natural fit. I never considered the audacity of a white man portraying a brown man. I knew a lot about his life, and Gandhi’s thoughts and actions aligned with my own thinking about social change. Indeed, my frequent involvement in nonviolent actions, such as my trip to war-torn Nicaragua in 1983, sponsored by Witness for Peace, were inspired by Gandhian principles, King’s work on behalf of civil rights, and Buddhist protests against the war in Vietnam. These activities prepared me to interact comfortably in the role of Gandhi before a variety of audiences.

Admiring and Chiding

Gandhi’s risk-taking and challenges to human rights violations exceed those of average folk. And unlike Jesus or the Buddha who lived in the ancient world, Gandhi rode in automobiles and used a telephone; students consider him accessible, belonging to an era they grasp. His civil disobedience teases them to interrogate the necessity to obey the law. His simple living contrasts with models of material success to which they aspire. His readiness to hazard personal injury, one upshot of his devotion to nonviolence, upsets students who claim a right to self-defense. Gandhi’s story, peppered with dilemmas and lifestyle choices to investigate, never fails to stimulate discussion and self-critiquing as students personalize Gandhi’s behavior, both admiring and chiding the man, and asking themselves: “Could I, should I, or would I behave like him?”

Roleplaying Gandhi jostles my thinking, too, arousing ethical self-assessment; it also spawns personal fatigue grounded in the folly of interpreting a human life as one of flawless sainthood. To view the Mahatma as moral paragon flattens his admirers’ self-images, as they inescapably fare poorly in comparison. Yet when portraying Gandhi, I am no outsider. I contact an interior excitement at the core of my being. Denied the opportunity to portray him, I would consider a profound personal deprivation, and yet that is not the entire story.

Twenty-eight years ago, I put on my Indian accent and clothes, then taught a European history class from Gandhi’s standpoint, as I imagined it. In that class sat Shannon, a friend of my daughter. After class, an amusing incident unfolded. Shannon left my room to walk across campus. My daughter, who also attended the school, saw her and yelled, “Have you seen my father today?” Shannon shot back about the bare-legged, bare-chested Gandhi look-alike she had just observed, “I have seen more of your father today than I ever care to see again.” While sometimes jealous of this cynosure, I too can say the same about Gandhi: I’ve witnessed enough.

On Gandhi’s seventieth birthday, Albert Einstein speculated, “Generations to come, it may well be, will scarce believe that such a man as this one ever in flesh and blood walked upon this Earth.”[7] Yes, his life sets a dizzying standard of virtue to emulate, a directional signal bidding us to take a morally right turn. While grateful for that signal calling us to turn toward him—embracing such integrity, spirituality, and effort—that signal also depletes me. To become Gandhi-like requires a radical turnaround whether attempted bit by bit or abruptly, a personal evolution or revolution I sadly spurn while still admiring the man I love to portray.

As a Gandhi portrayer, I know the impossibility of presenting a truly accurate interpretation of him. Nor can Carl Closs or Dean Malissa muster an authentic depiction of George Washington. This realization throws into question whether it is excusable to attempt to step into a great soul’s footwear with an eye toward producing a scrupulous portrayal, unable, as we are, to empathize adequately with anyone’s inner world, much less that of a highly evolved spiritual or political icon. If genuine empathy exists, it is perhaps best reserved for identification with another’s setbacks or suffering, such empathy more likely achievable by average folk.

And if admiration, different from empathy, nonetheless serves a function—to motivate and lure us to copy—I recognize that such copies or imitations are intrinsically unoriginal. Originals possess authenticity. If admiration calls us to copy our objects of affection, it also engenders an existential dilemma: to copy may demand abandoning authenticity, but resisting such imitation denies admiration’s allure and benefits.

Like other emotions, admiration calls us to action. It offers inducement to imitate, providing opportunities to experiment with the characteristics of the one whom we admire. Also, admiration is a tool to diagnose authenticity as well as phoniness. Sometimes it leads an admirer to adopt a few features of the idolized target while rejecting others. To portray the Mahatma, I daresay play at being him, offers me the opportunity to sift through my own inclinations, talents, and values and to explore the existential questions that surface in adolescence and resurface throughout life: To whom or what do I owe my highest loyalty? Do I have a purpose? What is worth laboring to achieve? If viewed as a tool for self-understanding, admiration frees us from experiencing as absolute the claims on our allegiance made by the Buddha, Jesus, or Gandhi. People we admire challenge us to determine priorities and commitments while simultaneously serving as a steppingstone to contacting and courting our true selves. And admiration invites me to ponder if it foolish or unseemly for a privileged white man to portray Gandhi.

I Am Not Brown

A few years ago, an Indian American student who learned that I portrayed Gandhi asked me to participate in an awards ceremony sponsored by the India Association of Rhode Island. Deserving students who entered the association’s Mahatma Gandhi Essay Competition were to receive acknowledgment for their award-winning essays. While dressed like Gandhi in a white dhoti and shawl, I was asked to say a few words at the RI State House using my Gandhi voice and accent, and then present one of the awards to a student. I found the event uncomfortable. First, I was portraying an Indian in front of a largely Indian audience. Second, there was little time to build rapport with those in attendance. Third, I was more prop than actor. Everyone was cordial, but my awkwardness led me to reassess the advisability of performing as Gandhi.

After the event, I asked myself this question: Does a white American who portrays Gandhi contribute to perpetuating our history of racism? My answer is YES. As a privileged white American male, I represent a race, gender, and dominant culture that demeans, batters, and subjugates people of color. Donning a dhoti and adding an Indian accent to impersonate the Mahatma ignores the power and arrogance of privilege to colonize a portion of humanity, a privilege that constructs a bubble around whiteness. Faking brown skin is presumptuous. Although portraying Gandhi has been good for me, leading to increased self-understanding, it no longer seems appropriate; it never was. Since George Floyd’s murder, now more enlightened about how white power pervades our society, I will no longer step into Gandhi’s sandals, attempting to approximate his viewpoint. Instead, lamentably, I will leave that to future portrayers, people of color stung by white domination, individuals perhaps better suited to interpret the life of the Great Soul, even if exacting portrayals will, necessarily, remain elusive.

©2023 Paul Graseck

All rights reserved

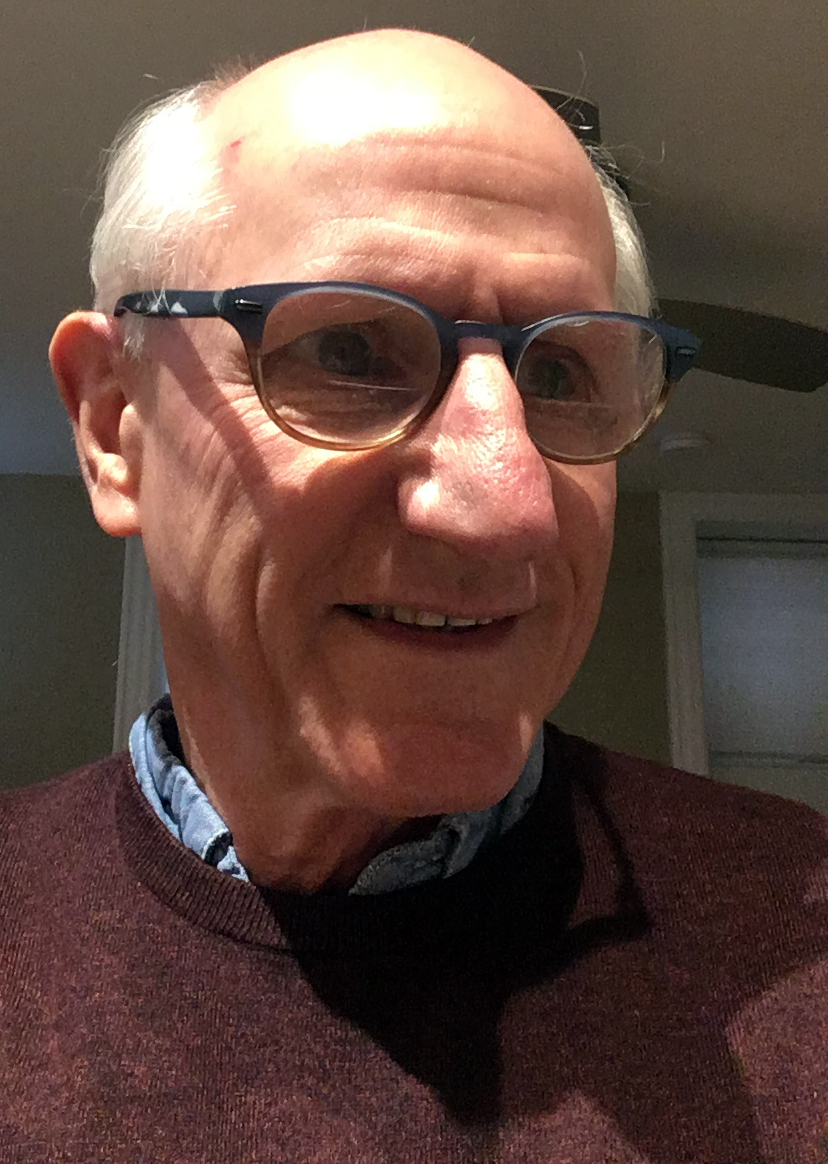

Paul Graseck…

…is an educator, activist, and character portrayer, who portrayed Gandhi for school and adult audiences. He also plays clarinet in an activist street band. Paul has published in Persephone, Kappan, History Matters, Kestrel, Star 82 Review, Friends Journal, The Decadent Review, Still Point Arts Quarterly, and elsewhere. Previously, he edited The Leader, a national magazine for social studies supervisors. Paul lives in Pomfret, Connecticut.

Notes

[1] Nathaniel Philbrick, Travels with George (New York: Viking, 2021), p. 283.

[2] Mohandas K. Gandhi, Gandhi on Non-violence: Selected texts from Mohandas K. Gandhi’s Non-violence in Peace and War, ed. Thomas Merton (New York: New Direction Publishing Corporation, 1964), p. 36.

[3] Eknath Easwaran, Gandhi the Man (Tomales, CA: Nilgiri Press, 1997), p. 145.

[4] The Bhagavad Gita, trans. By Eknath Easwaran (New York: Vintage Spiritual Classics, 2000), p. 16.

[5] Easwaran, Gandhi the Man, p. 145.

[6] Mohandas K. Gandhi, Young India, 31.12.1931.

[7] https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/131951-generations-to-come-will-scarce-believe-that-such-a-one.