If I have an headache, I generally take a pill. But are we really sure that only medicines are able to heal our illnesses? Deborah Alma, poet and poemedic, said no. Also poetry can give us a great hand to face our problems, in particular those that are hidden in our deepness. We had a brief chat about Deborah’s wonderful work and this is what came out.

Mendes: The theme of this issue is the healing power of art. Before asking you about The Emergency Poet, I would like to know your personal experience with art self-healing.

Deborah: That’s an interesting question and quite a difficult one to answer briefly. I think my own experience is like most people’s extremely varied, very common and often very unconscious.

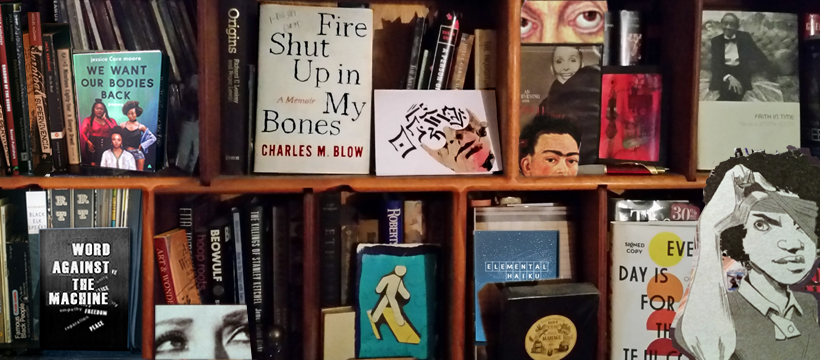

The moments that stand out for me I suppose were in the compulsion I felt to write myself through and out of an abusive and damaging relationship, watching my own grandmother’s solace in reading poetry after the death of her husband and as she was dying. I remember also being overwhelmed by an exhibition in London of the works of Frieda Kahlo and how bravely she painted her pain. I have worked for a few years with people with dementia and at the end of their lives using poetry.

For me, there is no doubt that art is where we can best connect with each other in ways that are intimate, empathetic and authentic.

MENDES: Now it’s the time of the Poemedic as you like to call yourself. A white coat, a stethoscope and a poetry book are the main objects you need when you ask your patients to open themselves up and then you suggest to them the right poem. What happens when patient and poem match each other?

Deborah: Ah this has been the most amazing thing for me! I had no idea when I started prescribing poetry just how much this process can work. People love to have a poem hand-picked for them after some careful listening. They see the gift and make it their own. It seems to bring a lot of joy, and sometimes relief and comfort.

Mendes: Why people are frightened about reading poems and how can people involved in culture help readers to start loving poetry?

Deborah: I think that something happens, at least in the UK in secondary school where often pupils are asked to examine texts as though they were a forensic scientist, pulling out the meaning and the poet’s intention, leaving the student with a sense that somehow poems are difficult, like a puzzle to be decoded rather than being asked to respond emotionally and intuitively. They also seem to stop writing creatively themselves and being a writer yourself is the easiest way into loving poetry.

I think that there is a certain amount of snobbery in the poetry world, that asserts that poetry is not for everyone, that likes to encourage this perception of difficulty. Certainly some poetry is ‘difficult’ and the reader is rewarded and flattered by understanding it, its clever tricks, its craft, its vocabulary; but instead of saying it is just for us few, I believe we can help others in. This comes from reading widely, from a developing confidence in approaching a poem and through being invited in. This is what I aim to do with Emergency Poet, invite them in.

Mendes: You worked also with people with dementia. How can it help, in this case, reading poetry?

Deborah: I have worked using poetry with people with dementia and also with people in care homes and in hospice care for the last five years. As a poet I do know something about what it is to be intimate and honest and authentic. The thread joining poetry and these areas of work for me is this intimacy and honesty. Poetry I believe, more than any other art, with the exception perhaps of music, (and they have much in common), speaks as though directly from one human being to another. It is about connection and empathy.

Most of the people that I’ve worked with who have some degree of dementia, are from the generation that learnt poetry by heart at school. As a poet working with a small group of people in a care home or day care centre I have often had the experience described so beautifully in Gillian Clarke’s poem Miracle on St David’s Day that describes the poet reading Wordsworth’s much-loved poem Daffodils in a care setting somewhere, where the words of the poem long ago learnt by heart , ignite something deep inside the mind of a long mute man;

“He is suddenly standing, silently,

huge and mild, but I feel afraid. Like slow

movement of spring water or the first bird

of the year in the breaking darkness,

the labourer’s voice recites The Daffodils.”

It is a gift and a privilege to be the one who brings this to a group of people. I worked with a group of people with sight-loss last year and as I started to read Masefield’s ‘I must go down to the sea again, to the lonely sea and sky…’ and to have at least twenty voices take it up with me, one woman reciting it word perfect all the way to the end was a joy to all present and it brings a tear to my eye even now as I write this and remember it.

Mendes: Best and the worst experience you have had with the Emergency Poet?

I think the best experiences I have had with Emergency Poet, and I have had so many, was when taking the ambulance to Bristol Southmead Hospital for a few days and parking near the other ambulances and prescribing poetry to patients, stressed staff and visitors . There was something very uplifting for people , (one woman still attached to her drip and in slippers) answering questions that were gentle, uplifting and being given the gift of a poem. It worked really well there. I’m starting to work in hospices prescribing poetry, which is wonderful and intense and extremely rewarding.

Bad experiences are usually to do with bad weather, wind , rain and cold! The hardest thing for me is to prescribe poetry to people who have never really read at all, not even as children.

Mendes: We always need a box of aspirin in our pockets. Who is, for you, the poetical aspirin? Can you suggest us any “everyday” poems?

Deborah: I have a few poems that I use very often; the poem I am prescribing a lot these days ( it has been a difficult year), is the beautiful poem Try to Praise the Mutilated World by Adam Zagajewski

Mendes: The ambulance is riding down the street. What and when is the next stop?

Deborah: It’s quiet over the winter because of the weather, but the next stop is to set up an inside surgery and run a workshop on compassion at a conference in London for Psychology and Psychological Therapies which will be fascinating for me. I will have fun having psycotherapists on my couch!

To know more about Deborah Alma and her work, you can visit her website The Emergency Poet, The world’s first and only mobile poetic first aid service.

Here are a few poems by Deborah Alma

Deep Pockets

I sit in the kitchen

in a yellow-striped dress

with deep pockets

thrusting my hands deep

there is string, a pin,

garden wire and three

sweet-pea seeds.

I sit sullen like a child.

On the table a roughly made

grey plate with flecks of blue

and four chocolate dainty cakes

and five of us in this house.

Pink Pyjama Suit

Five, I must have been,

just five, blonde kid

in my pink, shiny shalwar kameez.

Auntie, Karachi, pinched my cheeks,

Chorti pyara,

like a doll

like a little blonde doll.

Walk this way, try some dancing.

Behen! Now you have your little blonde doll

to play with!

Mummi-ji, I don’t want to wear it to school.

North London laughs too easily,

makes fools of us and this mix-up family, this

half-caste council-estate bastard.

Miss Minchin, one arm shorter than the other

knew how North London could laugh, and said:

Knock on all six doors and tell them

Miss Minchin says I must show the children

my clothes from Pakistan.

Mummi-ji, the glass on the doors is too high

and all those eyes

as I turn round and round, up on teachers’ tables

to twist in my pretty pink pyjama suit

like a little blonde doll.

On Sleeping Alone

oh my oh my what big teeth you have letters of love smelling of sandalwood in your special box of disappointment and raging not sleeping soundly remembering that you should be the start of the happy ever after story not the little girl swallowed whole to be saved by the woodman and his wielded axe

wolves in sheep’s clothing

grannies’ bonnets tied with a ribbon under their sweet little chins

now I sit tight on the lid

Pandora was not heavy in her hips like me not grounded by her own strong living days and nights

I am drawn instead to my own songs to let them sing in the fresh air love letters to myself wearing the blue slip with the butterfiles I take up the pretty teapot for one the scracthy pen the days the life floating lonely happy and sad

the blank sheets.

– Deborah Alma

© text, Mendes Biondo and Deborah Alma; poems Deborah Alma

What a marvelous thing! The Poemedic idea sounds like something Steve & I were kicking around one day. I’m so glad someone is actually doing it! What is so needed is permission to slow down, be intuitive and soft and emotional rather than attack everything like a pathogen to be obliterated. It takes the violence and sterility out of healing and allows it to be gentle and fecund, if a bit earthy & messy. Steve often says when I get a small cut, “Rub some dirt in it.” He’s being silly and boyish, but that’s always better than being paranoid and antiseptic, I think.

LikeLike