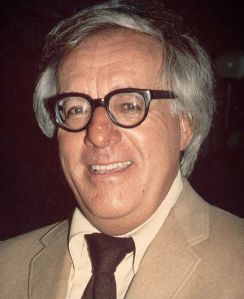

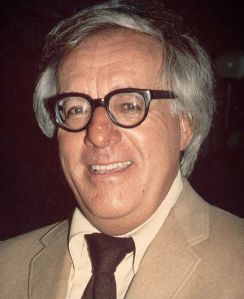

While there were many salutes to Ray Bradbury upon his death on June 5, 2012, we encountered none with as much warmth, insight and appreciation as this piece by Colin Blundell (colinblundell). Though it is far longer than our current 1,000 word limit ( one lesson experience has taught us is that the Blogosphere is largely a sound-bite world), we thought it was time to bring it out, dust if off and share it again. On reading this essay, you will understand why . . .

Forty years ago, I began teaching ‘English’ to 11-16 year-olds in a comprehensive school in a suburb of Luton, Bedfordshire UK—Stopsley High School. A class of 4th year boys was well on the way to defeating me till I discovered that reading Ray Bradbury short stories to them was a really good way of keeping them quiet for a whole lesson and even inspiring them to think and write. Ray Bradbury was the key that opened doors for these boys who had mostly been rejected by the system they found themselves enslaved by. Admittedly, by report, some of them later did a stretch in prison but not a few of them went on to get degrees, to become teachers and hold responsible jobs in local industry. I have sadly lost touch with all of them.

The short story that seemed to have the most immediate effect, and the one I always associate with that period of my life, was The Murderer from The Golden Apples of the Sun (1953). It was the story that perhaps meant most to me, one I could put my heart and soul into the reading thereof.

Music moved with him in the white halls. He passed an office door: ‘The Merry Widow Waltz’. Another door: ‘Afternoon of a Faun’. A third: ‘Kiss Me Again’. He turned into a cross corridor: ‘The Sword Dance’ buried him in cymbals, drums, pots, pans, knives, forks, thunder, and tin lightning. All washed away as he hurried through an anteroom where a secretary sat nicely stunned by Beethoven’s Fifth. He moved himself before her eyes like a hand; she didn’t see him. His wrist radio buzzed.

“Yes?”

“This is Lee, Dad. Don’t forget about my allowance.”

“Yes, son, yes. I’m busy.”

“Just didn’t want you to forget, Dad,” said the wrist radio. Tchaikovsky’s ‘Romeo and Juliet’ swarmed about the voice and flushed into the long halls.

Where are we? What’s going on? Forty years back there was no such thing as a mobile phone; the wrist radio is part of Ray Bradbury’s accurately terrifying vision of the future, which is now: the mobile phone is a symbol for the way life for many people seems to be threaded on messages from an imagined other place, messages, usually of no real consequence, that materialise to interrupt life while it is being lived, to divert attention from the concentrated flow of existence.

Once upon a time, you were able to move from experience to experience without the feeling that at any moment your flow was going to be interrupted by messages from an outer space which is not yours; life has changed and with it consciousness—it’s no longer a direct relationship between you and mountain, river, birdsong, zebra, touch of skin, and sensation of wind but something mediated by a mechanical drive to make contact with somebody to express the connection in some dull-witted way, or have it interrupted by somebody else’s account of their own experience of zebras and so on…

I do not remember that piped music was everywhere when I was growing up (I don’t think it was) but it’s more or less impossible to avoid the intrusiveness of the assault on the ears nowadays. The person with the switch assumes that it’s OK to bombard us with Muzak; most people don’t notice that it is washing over them—it’s the mechanical norm.

One might just consider oneself lucky to have Beethoven’s Fifth or L’après-midi d’un faune swarming about the long halls of the supermarket rather than the latest pop-crap but on the whole, instead of having others impose their banal choices on me, I prefer to organise my own listening schedule just when I want it to happen and not otherwise.

Ray Bradbury is simplistically referred to as a Science Fiction writer but it’s more the case that he is of that fraternity that seems to be plugged into the way things are going in fact rather than as fiction—those who are sufficiently tuned into human trends and weaknesses to understand where things are heading. H.G. Wells was another member of the clan.

“Prisoner delivered to Interview Chamber Nine.”

He unlocked the chamber door, stepped in, heard the door lock behind him.

“Go away,” said the prisoner, smiling. The psychiatrist was shocked by that smile. A very sunny, pleasant warm thing, a thing that shed bright light upon the room. Dawn among the dark hills. High noon at midnight, that smile. The blue eyes sparkled serenely above that display of self-assured dentistry.

“I’m here to help you,” said the psychiatrist, frowning. Something was wrong with the room. He had hesitated the moment he entered. He glanced around. The prisoner laughed. “If you’re wondering why it’s so quiet in here, I just kicked the radio to death.”

At length we find that our hero is Mr Albert Brock, who calls himself ‘The Murderer’. The psychiatrist, who intends to put him right, deems him violent, but Brock says that his violence is only towards ‘machines that yak-yak-yak…’

He quickly demonstrates his murderous intentions.

“Before we start…” He moved quietly and quickly to detach the wrist radio from the doctor’s arm. He tucked it in his teeth like a walnut, gritted, heard it crack, handed it back to the appalled psychiatrist as if he had done them both a favour. “That’s better.”

I often feel like doing this to mobile phones and other beeping implements on trains when my quiet reading is interrupted by them.

Deviant Behaviour

The psychiatrist asks Brock to talk about his deviant behaviour.

“Fine. The first victim, or one of the first, was my telephone. Murder most foul. I shoved it in the kitchen Insinkerator! Stopped the disposal unit in mid-swallow. Poor thing strangled to death. After that I shot the television set! … Fired six shots right through the cathode. Made a beautiful tinkling crash, like a dropped chandelier…”

“Suppose you tell me when you first began to hate the telephone.”

Because the telephone used to upset me as a child and because I would still rather not talk over the telephone I used to read the following explanation to my classes with extreme relish and rhetorical gusto, loudly and at increasing speed.

“It frightened me as a child. Uncle of mine called it the Ghost Machine. Voices without bodies. Scared the living hell out of me. Later in life I was never comfortable. Seemed to me a phone was an impersonal instrument. If it felt like it, it let your personality go through its wires. If it didn’t want to, it just drained your personality away until what slipped through at the other end was some cold fish of a voice, all steel, copper, plastic, no warmth, no reality.

It’s easy to say the wrong things on telephones; the telephone changes your meaning on you. First thing you know, you’ve made an enemy. Then, of course, the telephone’s such a convenient thing; it just sits there and demands you call someone who doesn’t want to be called. Friends were always calling, calling, calling me. Hell, I hadn’t any time of my own. When it wasn’t the telephone it was the television, the radio, the phonograph. When it wasn’t the television or radio or the phonograph it was motion pictures at the corner theatre, motion pictures projected, with commercials on low-lying cumulus clouds. It doesn’t rain rain any more, it rains soapsuds. When it wasn’t High-Fly Cloud advertisements, it was music by Mozzek in every restaurant; music and commercials on the buses I rode to work. When it wasn’t music, it was inter-office communications, and my horror chamber of a radio wrist watch on which my friends and my wife phoned every five minutes. What is there about such ‘conveniences’ that makes them so temptingly convenient? The average man thinks, Here I am, time on my hands, and there on my wrist is a wrist telephone, so why not just buzz old Joe up, eh? …I love my friends, my wife, humanity, very much, but when one minute my wife calls to say, “Where are you now, dear?” and a friend calls and says, “Got the best off-colour joke to tell you. Seems there was a guy…”

The climax came when Brock ‘…poured a paper cup of water into the intercommunications system’ at his office which shorted the electrics and had everybody running around not knowing what to do with themselves. Then Brock ‘got the idea at noon of stomping my wrist radio on the sidewalk. A shrill voice was just yelling out of it at me, This is People’s Poll Number Nine. What did you eat for lunch? I kicked the Jesus out of the wrist radio!’

A Solitary Revolution

Brock decided to ‘start a solitary revolution, deliver man from certain ‘conveniences’… Convenient for anybody who, out of boredom or aimlessness wanted a diversion.. “Having a shot of whisky now. Thought you’d want to know…” Convenient for my office, so when I’m in the field with my radio car there’s no moment when I’m not in touch…’

Why on earth should we ever wish to be ‘in touch’ with people, with contacts, with a million or so connections on the Internet, with ‘friends’ on Facebook? Why do we feel a need to communicate our insignificant ideas to anybody who will, we imagine, click in on a regular basis? Why am I writing this?

We are living the Twentieth Century illusion of total connectedness; we imagine an audience; we think we are making something happen. We are not. All that’s happened is that our concept of the world has changed; we like to think that we are all in it together—it could well be that this has affected the shape of ‘consciousness’ itself.

Why is it that the bosses imagine now that they can extend the working day 24 hours a day, 7 days a week by constantly having workers ‘in touch’? We let them get away with it.

In touch! There’s a slimy phrase. Touch, hell. Gripped! Pawed, rather. Mauled and massaged and pounded by FM voices. You can’t leave your car without checking in: “Have stopped to visit gas-station men’s room.” “Okay, Brock, step on it!” “Brock, what took you so long?” “Sorry, sir.” “Watch it next time, Brock.” “Yes, sir!”

Brock progressed his one-man revolution by spooning a quart of French chocolate ice cream—chosen because it was his favourite flavour— into the car radio transmitter.

The psychiatrist asked what happened next.

Silence

“Silence happened next. God, it was beautiful. That car radio cackling all day, Brock go here, Brock go there, Brock check in, Brock check out, okay Brock, hour lunch, lunch over, Brock, Brock, Brock… I just rode around feeling of the silence. It’s a big bolt of the nicest, softest flannel ever made. Silence. A whole hour of it. I just sat in my car, smiling, feeling of that flannel with my ears. I felt drunk with Freedom!”

Then Brock rented himself a ‘portable diathermy machine’. Now, if ever there was a sensible invention this is one. Often, especially on trains, I’ve thought to myself, “If only I had a ‘portable diathermy machine’, I could turn it on and silence all the inane chat, all the music blasting out of half-wit headphones, all the tapping and beeping that so disturbs me…”

I’ve even thought of trying to invent something that would do the trick. I once met a man who said he could help though there might be issues of legality. Brock, c’est Moi, I thought.

In the story, the effect of Brock’s murderous impulses was striking.

“There sat all the tired commuters with their wrist radios, talking to their wives, saying, ‘Now I’m at Forty-third, now I’m at Forty-fourth, here I am at Forty-ninth, now turning at Sixty-first.”

“I’m on the train…”

“One husband cursing, ‘Well, get out of that bar, damn it, and get home and get dinner started, I’m at Seventieth!’ And the transit-system radio playing Tales from the Vienna Woods, a canary singing words about a first-rate wheat cereal. Then—I switched on my diathermy! Static! Interference! All wives cut off from husbands grousing about a hard day at the office. All husbands cut off from wives who had just seen their children break a window! The Vienna Woods chopped down, the canary mangled! Silence! A terrible, unexpected silence. The bus inhabitants faced with having to converse with each other. Panic! Sheer, animal panic!”

“The police seized you?”

“The bus had to stop. After all, the music was being scrambled, husbands and wives were out of touch with reality. Pandemonium, riot, and chaos. Squirrels chattering in cages! A trouble unit arrived, triangulated on me instantly, had me reprimanded, fined, and home, minus my diathermy machine, in jig time.”

The psychiatrist, namby-pamby liberal democrat, suggests that Brock could have joined a club for gadget-haters, got up a petition, asked for a change in the law… Brock says he did all these things and more but he still found himself in an undemonstrative minority. The psychiatrist says that the majority rules.

“But they went too far. If a little music and ‘keeping in touch’ was charming, they figured a lot would be ten times as charming. I went wild! I got home to find my wife hysterical. Why ? Because she had been completely out of touch with me for half a day. Remember, I did a dance on my wrist radio? Well, that night I laid plans to murder my house… It’s one of those talking, singing, humming, weather-reporting, poetry-reading, novel-reciting, jingle-jangling, rockaby-crooning-when-you-go-to bed houses. A house that screams opera to you in the shower and teaches you Spanish in your sleep. One of those blathering caves where all kinds of electronic Oracles make you feel a trifle larger than a thimble, with stoves that say, ‘I’m apricot pie, and I’m done,’ or ‘I’m prime roast beef, so baste me!’ and other nursery gibberish like that. With beds that rock you to sleep and shake you awake. A house that barely tolerates humans, I tell you. A front door that barks: ‘You’ve mud on your feet, sir!’ And an electronic vacuum hound that snuffles around after you from room to room, inhaling every fingernail or ash you drop. Jesus God… ”

The psychiatrist suggests he minds his language.

“Next morning early I bought a pistol. I purposely muddied my feet. I stood at our front door. The front door shrilled, ‘Dirty feet, muddy feet! Wipe your feet! Please be neat!’ I shot the damn thing in its keyhole! I ran to the kitchen, where the stove was just whining, ‘Turn me over!’ In the middle of a mechanical omelet I did the stove to death. Oh, how it sizzled and screamed, ‘I’m shorted!’… Then I went in and shot the television, that insidious beast, that Medusa, which freezes a billion people to stone every night, staring fixedly, that Siren which called and sang and promised so much and gave, after all, so little…”

Having been arrested for destroying other people’s property, Brock was sent to the Office of Mental Health to be straightened out by a psychiatrist. Brock is unrepentant and says he’d do it all over again. The psychiatrist checks that he’s ready to take the consequences

“This is only the beginning,” said Mr. Brock. “I’m the vanguard of the small public which is tired of noise and being taken advantage of and pushed around and yelled at, every moment music, every moment in touch with some voice somewhere, do this, do that, quick, quick, now here, now there. You’ll see. The revolt begins. My name will go down in history!”

He’s prepared to admit that all gadgets were initially dedicated to making life less of a drudgery.

They were almost toys, to be played with, but people got too involved, went too far, and got wrapped up in a pattern of social behaviour and couldn’t get out, couldn’t admit they were in, even.

The gadgets have now become an unquestioned part of life. The next generation grows up with all the e-things and cannot understand old fogies like me wanting to, as they might see it, put the clock back.

Brock points out the irony that he ‘…got world-wide coverage on TV, radio, films… That was five days ago. A billion people know about me now. Check your financial columns. Any day now. Maybe to-day. Watch for a sudden spurt, a rise in sales for French chocolate ice cream!’

Brock looks forward to spending six months in jail, free from noise of any kind.

The psychiatrist’s diagnosis announced over the tannoy system is that Brock seemed convivial but ‘…completely disorientated’ refusing ‘… to accept the simplest realities of his environment and work with them…’

A Story to Shape the Soul

Re-reading Ray Bradbury’s brilliant short story on the day I heard of his death at 91, I realise, not for the first time, how much it has shaped my being; my disgust with the way the world is now, my refusal to compromise, my sense of horror at the way people are sucked into A Influences and diverted by gadgetry from the things that really matter: the life of the soul, responses to Nature and all that comes under the heading of Understanding properly nurtured by Knowledge and Being… Indiscriminate working with the realities of one’s environment means giving in to crass stupidity, mass resignation to the way things are fostered by Big Business brain-washing and the endless traps of Capitalism.

Accept nothing unless it nurtures the soul. Verify everything for yourself, says Gurdjieff…

Brock walks cheerfully to prison looking forward to a nice ‘bolt’ of silence. Meanwhile for the psychiatrist normal life resumes…

Three phones rang. A duplicate wrist radio in his desk drawer buzzed like a wounded grasshopper. The intercom flashed a pink light and click-clicked. Three phones rang. The drawer buzzed. Music blew in through the open door. The psychiatrist, humming quietly, fitted the new wrist radio to his wrist, flipped the intercom, talked a moment, picked up one telephone, talked, picked up another telephone, talked, picked up the third telephone, talked, touched the wrist-radio button, talked calmly and quietly, his face cool and serene, in the middle of the music and the lights flashing, the two phones ringing again, and his hands moving, and his wrist radio buzzing, and the intercoms talking, and voices speaking from the ceiling. And he went on quietly this way through the remainder of a cool, air-conditioned, and long afternoon; telephone, wrist radio, intercom, telephone, wrist radio, intercom, telephone, wrist radio, intercom, telephone, wrist radio, intercom, telephone, wrist radio, intercom, telephone, wrist radio…

End of a Story…

What I would dearly love to know is whether The Murderer penetrated the soul’s of the lads I taught all those years ago as much as it has penetrated mine. Amongst others, Paul, Martin Chris, Richard, Stephen, John and also Chris & Pete who went off to swim unwillingly amongst the stars in the 1970’s.

If any of you should chance to read this, please get in touch, as they say…

– Colin Blundell

© 2012, essay and portrait (below), Colin Blundell, All rights reserved

COLIN BLUNDELL (colinblundell) ~ is a generous and informed writer whoand covers the range: poetry, fiction, and philosophical tomes. When he isn’t writing, he is busy making music and hand-made paperback books, painting watercolours, and going on long-distance motorbike treks. He’s left off being a wage-slave in 1991. He is now an independently teaching Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP), Accelerated Learning, Steven Covey’s Seven Habits, Change Management, Problem-solving and Time Management, and the art and practice of the Enneagram.

COLIN BLUNDELL (colinblundell) ~ is a generous and informed writer whoand covers the range: poetry, fiction, and philosophical tomes. When he isn’t writing, he is busy making music and hand-made paperback books, painting watercolours, and going on long-distance motorbike treks. He’s left off being a wage-slave in 1991. He is now an independently teaching Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP), Accelerated Learning, Steven Covey’s Seven Habits, Change Management, Problem-solving and Time Management, and the art and practice of the Enneagram.

Thank you for sharing the beauty and inspiration: